Visual Storytelling

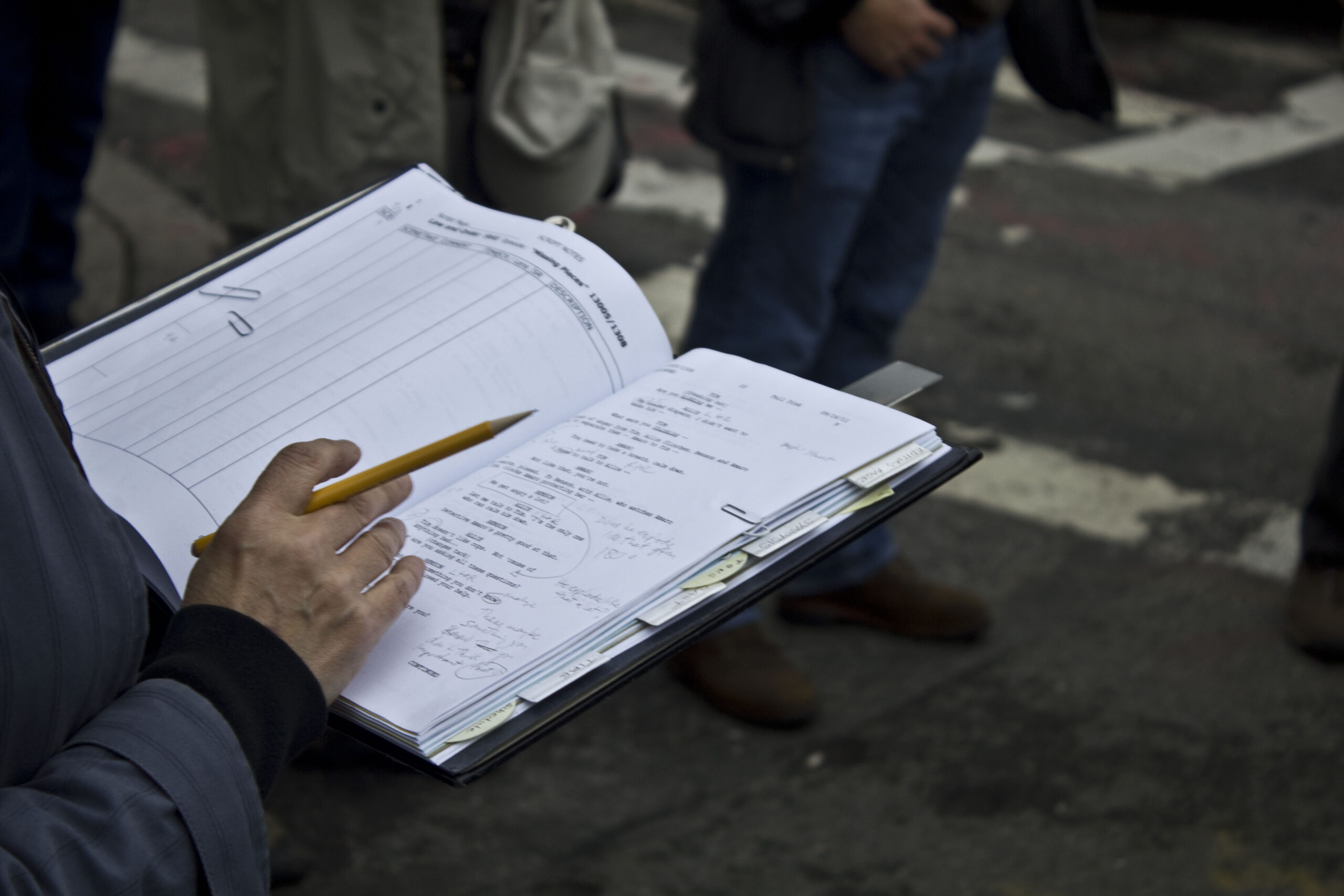

Visual storytelling refers to the images screenwriters use to convey a tone, emotion and style of a film. They show - rather than tell - the reader what’s happening in that scene and describe the character’s actions in such a way we know exactly what’s going through their minds. So, although it’s the cinematographer’s job to visually support an idea in practice, the basis comes from the screenwriters themselves.

Visual moments are the hallmarks of the film industry – they depend on a writer’s ability to write visual moments that are aesthetically appealing. As a scriptwriter, you should define what it is you want the director and actor to express – visually. Give them the general idea and a good director and cinematographer will know how to follow your train of thought, or even better, provide a new direction that feeds off from your original one.

Continue reading

This content is restricted to IMIS members.

Apply to become a member and get access to our knowledge base, past event videos, the Member Directory and more…

Existing members please log in here.